Securing the airway in neonates with cleft pathology challenges even experienced anesthesiologists. A protective palatal obturator offers a simple mechanical strategy to shield vulnerable mucosa and stabilize the laryngoscopy trajectory during oral intubation. In a randomized comparison of a customized device versus standard practice in newborns undergoing cleft lip procedures, investigators quantified procedural performance and tissue safety outcomes, offering practical guidance for perioperative teams.

This article synthesizes what a protective obturator adds to neonatal airway management, how to operationalize customization, and where the approach may fit in everyday practice. We translate the controlled trial into pragmatic steps for preoperative planning, device fabrication, and intraoperative use, while outlining training, safety checks, and audit metrics that enable teams to adopt, measure, and continuously improve this technique.

Why protect the neonatal airway in cleft surgery

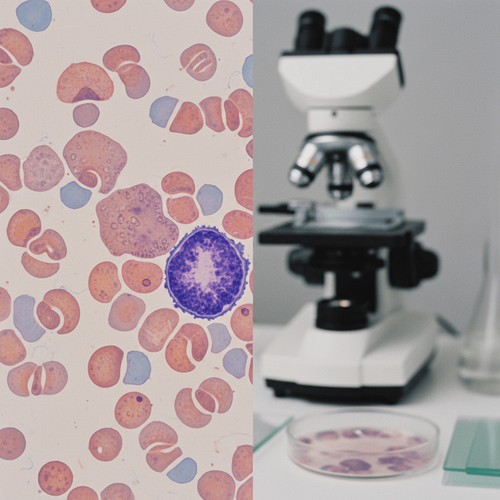

Newborns with cleft anatomy present a narrow margin for error during Neonatal Airway Management. Laryngoscopy can abrade fragile palatal edges and destabilize the line of sight, increasing the risk of bleeding and edema that compromise ventilation. A customized protective palatal obturator aims to shield mucosa and guide the endotracheal tube path, reducing soft tissue contact and improving control. By creating a smooth, protective surface across the cleft, the obturator may help preserve visualization while minimizing jostling at critical steps.

Neonatal Endotracheal Intubation has distinct physiologic constraints, including rapid desaturation, limited apnea tolerance, and high vagal tone. These factors amplify the stakes of first-pass performance and gentle tissue handling. In this context, a device that reduces mucosal trauma and streamlines tube advancement could improve both safety and efficiency. The randomized comparison linked to cleft lip surgery focuses on quantifiable endpoints that matter to clinical teams, including first-pass success, time to secure the airway, and periprocedural injury.

Evidence derived from a Randomized Controlled Trial is particularly informative for implementation because it tests the device in a controlled, protocolized environment while preserving clinical realism. Although neonatal cases are often individualized, a standardized workflow can still reduce variability and error. For anesthesiologists and surgeons, the essential questions are feasibility, reproducibility, and safety signals that justify training and procurement. The protective obturator addresses these questions by integrating with familiar laryngoscopy techniques rather than replacing them.

Beyond intraoperative efficiency, the guiding principle is Patient Safety. Any adjunct employed in a small airway must avoid new hazards, such as obstruction, aspiration, or impaired mask ventilation. Customization that respects neonatal anatomy and surgical goals can mitigate these risks while maintaining operational simplicity. The balance is delicate, but a well-designed obturator can serve as a low-profile safeguard for mucosa and a facilitator for predictable tube passage in the early seconds that decide outcomes.

What the trial compared

The randomized comparison evaluated a customized protective palatal obturator used during oral intubation against standard laryngoscopy without the device. Procedural outcomes included First-Pass Success, intubation time, need for adjunct maneuvers, and mucosal integrity endpoints such as bleeding or visible abrasion. Secondary observations captured ease-of-use and potential interference with standard equipment. This structure enables translation into practical checklists and operating room readiness plans.

While neonatal cleft surgery is heterogeneous, the inclusion framework centered on newborns scheduled for cleft lip procedures, where mouth opening, tissue vulnerability, and instrument access interplay. The results focus on operational metrics that perioperative teams can audit locally. By anchoring outcomes in time stamps and observable tissue events, the comparison supports targeted quality improvement efforts and informed device selection. The dataset complements case-based experience with a more standardized signal for practice.

Importantly, the evaluation did not require changing primary laryngoscopy devices or anesthetic approaches; instead, it added a protective interface that can be incorporated into a routine setup. This is a critical point for adoption, as teams benefit most from adjuncts that align with existing workflows. The ability to integrate with direct or Video Laryngoscopy preserves clinician choice while testing whether protection confers measurable gains. Consistency across operators and cases provides a fair test of feasibility.

Readers can access the primary report on PubMed to review inclusion criteria, device fabrication details, and endpoint definitions. For adoption, local teams should map the reported outcomes to their own baselines, targeting similar measures and time windows. Doing so allows apples-to-apples comparison and transparent performance tracking. The focus is not on a single metric in isolation but on an integrated profile of intubation efficiency and tissue safety.

Why a protective interface matters

Neonates with Cleft Lip And Palate exhibit discontinuity of oral tissues that funnels instruments into irregular paths. Contact points become focal stressors that can shear mucosa, bleed, and obscure the laryngeal view precisely when the tube must pass. A protective obturator transforms this geometry into a more uniform surface, distributing contact forces and smoothing tube tracking. In addition, a stable interface can reduce variability in instrument angle and depth during laryngoscopy, promoting reproducibility.

From a systems perspective, creating a consistent airway corridor improves human factors. Predictable tactile feedback and reduced soft tissue drag can decrease cognitive load during the most time-sensitive seconds of induction. In complex cases, every second that preserves oxygen reserves and every millimeter that avoids abrasion matters. By reducing friction literal and figurative the device supports the team in preserving focus on core tasks such as glottic visualization and tube verification.

Neonatal airways tolerate few attempts; multiple passes escalate desaturation risk, hemodynamic instability, and oropharyngeal injury. If a device can improve first-pass metrics and lower the chance of Mucosal Injury, it may shorten time to secure ventilation and stabilize the physiologic trajectory of the case. Clinical value arises not only in fewer adverse events but also in fewer unplanned deviations, such as switching devices midstream or escalating to surgical airways. Even when benefits are modest, the downstream effect on reliability can be meaningful.

Finally, protection may pay dividends beyond induction. Limiting palatal trauma early may translate to less edema, fewer dressing challenges, and fewer postoperative care adjustments that complicate recovery. While the trial concentrates on intraoperative metrics, teams can reasonably extend their audit to capture early postoperative bleeding, oximetry variability in recovery, and need for suctioning. These measures connect procedural details to outcomes that families and surgeons care about.

From device design to operating room workflow

Customization is the core enabler. The protective obturator must fit the neonatal palate, bridge the cleft without impingement, and remain low-profile to avoid obstructing laryngoscopy. Several fabrication pathways are viable, depending on institutional resources. Traditional dental impression methods can yield a quick thermoplastic or acrylic insert, while digital workflows use scanning and rapid prototyping to enhance precision. Regardless of method, each unit should be labeled, inspected, and verified for fit prior to induction.

Preoperative planning begins in clinic or pre-anesthesia assessment. Coordination between anesthesia, surgery, and dental or maxillofacial teams ensures timely fabrication and sterilization. A succinct protocol that specifies sizing, orientation markings, and packaging minimizes ambiguity on the day of surgery. Teams should incorporate the device into their airway cart checklist, assigning responsibilities for placement, retrieval, and documentation. Clear role delineation reduces last-minute delays and confusion.

In the operating room, placement occurs immediately before laryngoscopy. The obturator is seated gently to overlay the cleft edges, with attention to tongue position and secretions. Mask ventilation should be reassessed after placement to confirm no unexpected leak or obstruction. While an obturator is not an airway seal, it should not interfere with baseline ventilatory maneuvers. Laryngoscopy then proceeds as usual, with the operator mindful of the protective surface guiding the blade and tube.

Verification steps mirror standard practice. After tube placement, end-tidal CO2 confirmation and lung auscultation remain mandatory. The obturator is removed once the tube position is secure and taping is complete to avoid retention. A formal mucosal check documents any contact marks or bleeding. This small addition to the airway time-out reinforces safety culture and creates a traceable record for quality improvement.

Fabrication checklist

Successful customization begins with standardized data capture and a reliable manufacturing pathway. The following checklist can help teams stand up a service with predictable turn-around times and quality control. It is designed to be adaptable to either traditional or digital methods and to the scale of each institution. The goal is a device that is easy to place, atraumatic, and compatible with the chosen laryngoscopy approach.

- Patient data: weight, gestational age, cleft configuration, mouth opening, and tongue posture.

- Impression or scan: ensure minimal gag stimulus and safe positioning; document landmarks.

- Material selection: biocompatible, smooth-finish, sterilizable; low thickness to preserve space.

- Design features: rounded edges, orientation markings, and a gentle palatal arch contour.

- Trial fit: verify seating and stability on a model or intraorally in a controlled setting.

- Sterilization: choose method compatible with material; package and label with size and ID.

- Documentation: include a brief use guide in the airway cart and record-keeping template.

Intraoperative use steps

A concise, stepwise approach helps standardize performance under time pressure. The device should be seen as a protective interface rather than a new airway instrument. Attention to preoxygenation, depth of anesthesia, and positioning is unchanged. What changes is the contact surface and the potential trajectory smoothing for blade and tube passage. The steps below assume a conventional induction with clinician choice of direct or video laryngoscopy.

- Prepare the airway cart with the obturator, primary laryngoscope, backup device, and suction ready.

- Preoxygenate and induce as per protocol, ensuring readiness for rescue strategies.

- Seat the obturator to cover the cleft edges; reassess mask ventilation for adequacy.

- Proceed with laryngoscopy, using the obturator surface to minimize mucosal contact.

- Advance the tube along the smoothed corridor; confirm placement with capnography and auscultation.

- Secure the tube, then remove and account for the obturator; perform a mucosal integrity check.

- Document time to intubation, number of attempts, adjuncts used, and any tissue findings.

Human factors and training

Training should emphasize muscle memory in device placement and removal, awareness of the altered tactile environment, and communication cues. Simulation with manikins or 3D-printed models can accelerate learning without patient risk. Including surgeons and circulating nurses in brief drills fosters shared mental models and smoother handoffs. A single-page visual aid at the airway cart can reinforce correct orientation and removal timing.

Human factors also extend to cognitive load management. Assign a prompt for the mucosal check after tube taping and before surgical prep begins. Build a habit of verbal confirmation that the obturator has been removed and documented; count it like a surgical instrument. These micro-practices convert a new tool into an integrated element of the safety ecosystem. Over time, they reduce variability and build trust in the workflow.

Clinical implications, adoption, and audit

For perioperative teams, the central question is when to use the obturator and how to measure impact. Candidate cases include neonates with cleft anatomy where laryngoscopy is anticipated to contact mucosa directly. A straightforward adoption path is to introduce the device for primary intubations in scheduled cleft lip procedures and collect baseline metrics prospectively. Over a small series, teams can review performance and fine-tune fabrication and placement.

Metrics should mirror those reported in the trial to allow benchmarking. Core measures include first-pass success, time to intubation from blade insertion to capnography confirmation, number of attempts, and incidence of visible bleeding or abrasions. Additional measures might include desaturation episodes, heart rate changes, and any device interference with laryngoscopy. A short post-induction survey of operator ease-of-use can capture subjective workload and perceived benefit.

When choosing primary instruments, the obturator should remain compatible with both direct laryngoscopy and Device-Assisted Intubation techniques. Teams may prefer video laryngoscopy for its teaching value and consistent optics, but alignment with operator expertise is paramount. Regardless of device, a protection-first mindset supports gentle, deliberate movements that prioritize tissue integrity. The obturator does not replace the need for optimal positioning, suction readiness, or backup plans.

Data feedback loops close the implementation cycle. A monthly dashboard can display rates of first-pass success, mucosal injury, and time-to-tube across eligible cases. Outliers should prompt case reviews to identify modifiable factors, such as obturator fit, secretion management, or positioning. Transparent sharing at multidisciplinary meetings builds collective skill and confidence, while preserving patient-centered safeguards.

Risk assessment and mitigation

Any addition to the airway pathway requires a preemptive risk inventory. Potential failure modes include poor fit leading to dislodgement, unexpected interference with mask seal, or delayed removal after tube fixation. Mitigation strategies include pre-induction fit checks, dual confirmation of removal, and a clearly visible orientation mark. Material selection should prioritize smooth edges and a finish that resists secretion adherence to minimize aspiration risk.

Documentation should capture both successes and near-misses. A near-miss log can reveal patterns faster than rare adverse events, guiding small iterative changes that compound over time. Institutions with incident reporting systems can tag cases involving the obturator to permit targeted review. Where feasible, integrate barcoding or unique identifiers for traceability across sterilization, storage, and use.

Where this fits in perioperative care

The protective obturator is best viewed as a component of comprehensive Perioperative Care. It complements meticulous induction planning, optimal positioning, and calm, choreographed teamwork. As a low-tech adjunct, it can be deployed quickly with minimal capital investment, making it attractive for a range of settings. Its customization requirement is a manageable trade-off for the potential gains in consistency and tissue protection.

In resource-constrained environments, simple thermoplastic approaches may suffice, provided they meet biocompatibility and sterilization standards. Academic centers may leverage digital modeling for precision and reproducibility. Both pathways can deliver effective protection when anchored in good processes and shared expectations. What matters most is not the sophistication of fabrication but the reliability of the workflow that surrounds it.

Communication with families and teams

Transparent discussions with caregivers can frame the obturator as a protective measure used during intubation to reduce tissue contact. While the details of laryngoscopy may be complex, families appreciate concrete steps taken to lower risk. Include the device in consent discussions as part of the airway plan, and summarize its use and tolerance in postoperative notes. Clear documentation fosters continuity and shared understanding among clinical teams.

Internally, concise debriefs after cases accelerate learning. What worked smoothly, what required improvisation, and how did the device interact with the chosen laryngoscope? Five-minute discussions captured in a simple template can yield tangible improvements within a few cases. The habit of structured reflection builds a culture where small enhancements translate into durable safety gains.

Limitations and future directions

Like any single-center evaluation, generalizability may be constrained by local fabrication methods, operator experience, and case mix. The neonatal airway is unforgiving, and benefits observed in controlled settings may attenuate under different circumstances. Comparative effectiveness across different laryngoscopy devices and blade geometries warrants further exploration. Longitudinal follow-up could assess whether reduced intraoperative tissue trauma translates into measurable postoperative recovery advantages.

Future directions include standardizing sizing schemas, developing universal orientation cues, and testing materials that balance flexibility with protective strength. Multicenter collaborations can expand the evidence base and clarify where the device has the largest impact. Integration with simulation curricula may enhance training, particularly for rotating trainees who face steep learning curves. These steps can refine both the device and the system that enables it.

Reflective synthesis

The customized protective palatal obturator represents a pragmatic, safety-centered adjunct for neonatal intubation in cleft procedures. By smoothing tissue interfaces and guiding instrument paths, it targets the moments that define success or failure in small airways. The randomized comparison offers a structured view of feasibility and performance, supplying metrics that perioperative teams can adopt for local audit. With deliberate fabrication, disciplined workflow, and focused training, the approach can be integrated without disrupting established practices.

Limitations remain, including variable fit, material choices, and operator familiarity that can influence outcomes. Yet the implementation path is clear: define eligible cases, standardize fabrication, measure what matters, and iterate. In doing so, teams can convert an elegant idea into a dependable practice that protects the most vulnerable tissues during the most critical seconds. The result is not just safer intubations, but a tighter, more resilient perioperative system.

LSF-0043034934 | October 2025

How to cite this article

Team E. Customized palatal obturator for neonatal intubation safety. The Life Science Feed. Published November 5, 2025. Updated November 5, 2025. Accessed January 31, 2026. .

Copyright and license

© 2026 The Life Science Feed. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all content is the property of The Life Science Feed and may not be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission.

Fact-Checking & AI Transparency

This summary was generated using advanced AI technology and reviewed by our editorial team for accuracy and clinical relevance.

References

- de Carvalho M, Monteiro FF, Costa M, et al. Customized protective palatal obturator for intubation in newborns in cleft lip surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Journal Name. 2025;Volume(Issue):Pages. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40981509/.