The traditional disease-centered approach to geriatric care often falls short. We treat individual conditions, but miss the bigger picture of overall function and well-being. A recent study highlights the importance of "intrinsic capacity" - the composite of all physical and mental capacities within an individual - as a stronger predictor of outcomes than any single diagnosis. The question is: can we move beyond the problem list and adopt a more holistic approach to geriatric care, as advocated by the WHO's Healthy Ageing strategy?

This research adds weight to the argument that integrated assessments of intrinsic capacity should be central to how we evaluate and manage older inpatients, potentially leading to more effective and personalized interventions. However, practical challenges remain in implementing these assessments at scale.

Clinical Key Takeaways

lightbulb

- The PivotGeriatric assessment should prioritize overall functional capacity rather than focusing solely on individual diseases.

- The DataEach additional domain of impaired intrinsic capacity significantly increased the risk of geriatric syndromes (OR 1.46, 95% CI 1.29-1.66).

- The ActionImplement standardized assessments of intrinsic capacity, including cognition, psychological state, mobility, nutrition, and sensory function, in routine inpatient geriatric evaluations.

Intrinsic Capacity Assessment

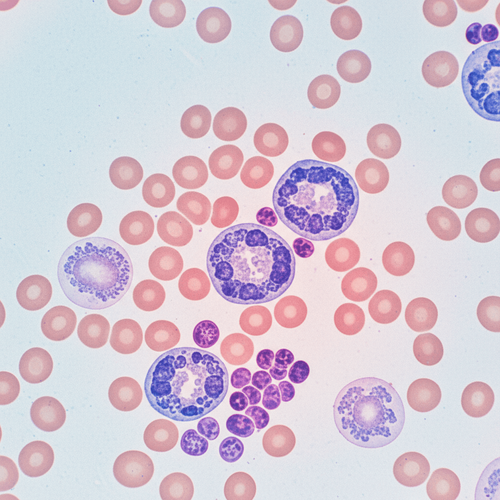

The concept of intrinsic capacity (IC) offers a framework for assessing the overall health and functional reserve of older adults. It moves beyond a simple list of diagnoses to consider the interconnectedness of various physiological and psychological systems. Domains typically included in IC assessment are cognition, psychological state, mobility, nutrition, and sensory function. Decline in one or more of these areas can signal increased vulnerability to adverse outcomes like falls, hospitalizations, and mortality. This study underscores that the cumulative effect of deficits in these domains is a powerful predictor of geriatric syndromes and functional decline in older inpatients.

The study itself examined the association between IC domains and adverse outcomes in a cohort of older adults admitted to an acute geriatric unit. Patients were assessed for deficits in each of the five IC domains, and the cumulative number of deficits was correlated with the presence of geriatric syndromes (e.g., falls, delirium, pressure ulcers) and functional status at discharge. The results showed a clear dose-response relationship: the more domains of IC that were impaired, the higher the risk of adverse outcomes. Specifically, each additional domain of impairment significantly increased the odds of experiencing one or more geriatric syndromes (OR 1.46, 95% CI 1.29-1.66). This suggests that interventions targeting multiple domains of IC may be more effective than focusing on individual risk factors.

Comparison to Guidelines

While not explicitly contradicting existing guidelines, this study advocates for a shift in emphasis. Current guidelines, such as those from the American Geriatrics Society (AGS) and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), typically recommend comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) for older adults at risk of functional decline. CGA includes evaluation of medical, psychological, and social factors, as well as functional status. However, the focus is often on identifying specific problems and addressing them individually. The AGS Beers Criteria, for example, concentrates on potentially inappropriate medications, and the NICE guidelines on falls prevention recommend targeted interventions based on identified risk factors. While these approaches are valuable, they may not fully capture the complex interplay of factors that contribute to overall functional decline.

The WHO's Integrated Care for Older People (ICOPE) guidelines represent a more aligned approach, promoting person-centered care that considers the individual's intrinsic capacity and functional abilities. However, implementation of the ICOPE guidelines remains a challenge in many healthcare settings. This study provides further evidence to support the adoption of IC-based assessments as a key component of CGA, potentially leading to more effective and personalized care plans. Integrating IC assessment into existing workflows could improve risk stratification and resource allocation for older adults.

Study Limitations

Like all research, this study has limitations. The study was conducted in a single center, which limits its generalizability to other populations and healthcare settings. The sample size, while reasonable, could be larger to provide greater statistical power. Furthermore, the cross-sectional design precludes any conclusions about causality; it is possible that the presence of geriatric syndromes contributes to the decline in intrinsic capacity, rather than the other way around. Another potential limitation is the reliance on observational data, which may be subject to biases and confounding factors.

Finally, who funded this research? Was there any industry involvement or conflict of interest declared by the authors? Transparency in funding is paramount to ensure that the research is unbiased. Without this information, it is difficult to fully evaluate the validity of the findings.

Clinical Implications

Implementing comprehensive geriatric assessments including intrinsic capacity can strain resources. It takes time and trained personnel, and many hospitals are already operating at capacity. Will insurers reimburse for these expanded assessments? The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) may need to revise coding and payment policies to incentivize the adoption of IC-based assessments. Furthermore, electronic health records (EHRs) need to be adapted to facilitate the collection and analysis of IC data.

If we identify patients with diminished intrinsic capacity, what interventions are most effective and cost-efficient? Are we simply creating more work without improving patient outcomes? The ideal model should include a multidisciplinary team, including physicians, nurses, therapists, and social workers, to address the various domains of IC. It also necessitates stronger integration with community-based services to provide ongoing support after discharge. Addressing these systemic challenges is crucial to realizing the full potential of IC-based geriatric care.

From a workflow perspective, consider the burden on hospital staff. Current geriatric assessment is already time-intensive. Adding a formal intrinsic capacity evaluation requires additional training and documentation. Can existing staff absorb this additional workload, or will hospitals need to hire more geriatric specialists? The answer to this question directly impacts the feasibility of widespread implementation.

LSF-9718626114 | December 2025

How to cite this article

O'Malley L. Intrinsic capacity as a predictor of geriatric outcomes. The Life Science Feed. Published January 20, 2026. Updated January 20, 2026. Accessed January 31, 2026. .

Copyright and license

© 2026 The Life Science Feed. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all content is the property of The Life Science Feed and may not be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission.

Fact-Checking & AI Transparency

This summary was generated using advanced AI technology and reviewed by our editorial team for accuracy and clinical relevance.

References

- Cesari, M., Araujo de Carvalho, I., Amuthavalli Thiyagarajan, J., Azzopardi, C., Bartosch, O., Beard, J., ... & Hoogendijk, E. O. (2018). Evidence for the definition of intrinsic capacity in aging. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 73(12), 1688-1693.

- World Health Organization. (2015). World report on ageing and health. World Health Organization.

- American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on Healthcare for Older Adults. (2012). Comprehensive geriatric assessment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 60(1), 183-193.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2015). Falls in older people: assessing risk and prevention. NICE guideline CG161.