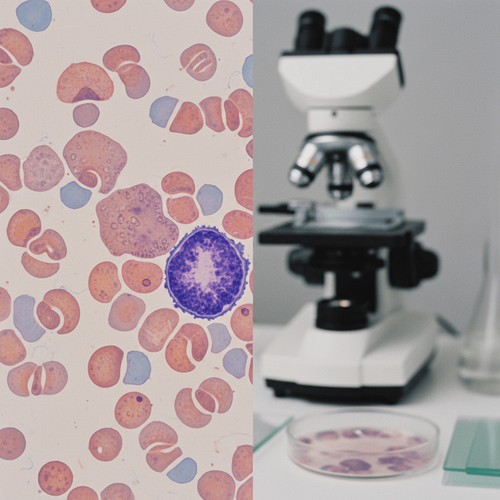

The creeping specter of antibiotic resistance demands constant vigilance, especially in common conditions like atopic dermatitis. We've all seen it: the go-to topical antibiotic that seemed to clear everything now barely touches the infection. A recent study from the UK highlights this concerning trend, specifically regarding Staphylococcus aureus resistance in patients with atopic dermatitis. This isn't just an academic exercise; it directly impacts your prescribing habits and patient outcomes on a day-to-day basis.

The implications of widespread resistance extend beyond individual treatment failures. It forces escalation to systemic antibiotics, with their attendant risks and costs. More importantly, it underscores the need for a more judicious approach to topical antimicrobial use.

Clinical Key Takeaways

lightbulb

- The PivotFusidic acid should no longer be considered a universally reliable first-line treatment for suspected Staphylococcus aureus infections in atopic dermatitis.

- The DataThe study showed a significant increase in fusidic acid resistance among Staphylococcus aureus isolates from atopic dermatitis patients in the UK region studied. Specific resistance rates varied, but the trend was clearly upward.

- The ActionConsider local resistance patterns and, where possible, obtain bacterial cultures and sensitivities before initiating topical antimicrobial therapy in recalcitrant cases. Prioritize mupirocin or consider alternative topical agents based on local antibiograms.

Guideline Context

Current guidelines, such as those from the National Eczema Association, often recommend topical antibiotics like fusidic acid or mupirocin as first-line treatments for suspected secondary bacterial infections in atopic dermatitis. However, these recommendations predate the widespread increase in antimicrobial resistance that we're now witnessing. Specifically, the rise in fusidic acid resistance directly challenges the common practice of empirically prescribing this agent without culture data. This study reinforces the need for guideline updates that reflect regional resistance patterns and promote antimicrobial stewardship.

We need to consider that these guidelines were written in a different era. The assumption of near-universal sensitivity to common topical antibiotics is no longer valid. It's time for a more nuanced approach, incorporating local antibiograms into our clinical decision-making.

Study Details

The UK-based study investigated Staphylococcus aureus isolates from patients with atopic dermatitis. The researchers collected samples from infected skin lesions and determined the antibiotic susceptibility profiles of the isolated bacteria. What they found was a significant increase in resistance to commonly used topical antibiotics, particularly fusidic acid. The study design involved a regional surveillance approach, capturing data over a defined period to assess trends in antimicrobial resistance within this patient population. While the specific methodology is sound, the geographical limitation raises questions about generalizability to other regions with potentially different antibiotic usage patterns.

Resistance Patterns

The observed increase in fusidic acid resistance is alarming. While specific percentages varied depending on the region and time period studied, the overall trend was clear: Staphylococcus aureus isolates from atopic dermatitis patients are becoming increasingly resistant to this once-reliable antibiotic. This shift necessitates a change in our approach to managing these infections. We can't simply continue prescribing fusidic acid as a default option and expect it to work. Furthermore, the study highlights the potential for cross-resistance, where resistance to one antibiotic may confer resistance to others. This underscores the importance of using antibiotics judiciously to prevent the further spread of resistance.

Study Limitations

Before we overhaul our prescribing habits, let's acknowledge the study's limitations. It's a regional study, and resistance patterns can vary significantly based on local antibiotic usage. The sample size, while adequate, could be larger to provide more robust statistical power. Furthermore, the study doesn't address the underlying causes of the increased resistance. Is it due to overuse of topical antibiotics? Poor patient adherence? Or other factors? Without understanding the root causes, it's difficult to implement effective strategies to combat resistance. The authors also did not explore the impact of specific emollient use on skin colonization or infection rates which can be a confounding variable. Finally, the financial model behind this research is not disclosed, so there is potential for bias based on funding sources.

Alternative Strategies

So, what do we do on Monday morning? First, become familiar with the local antibiogram. Know the resistance patterns in your community. Second, consider bacterial cultures and sensitivities, especially in recalcitrant cases. This will allow you to tailor your antibiotic selection to the specific organism and its susceptibility profile. Mupirocin remains a reasonable alternative, but resistance to mupirocin is also increasing in some areas, so proceed with caution. Topical corticosteroids can help manage inflammation which can secondarily reduce microbial colonization as well. Systemic antibiotics should be reserved for severe infections or those unresponsive to topical therapy.

Beyond antibiotic selection, emphasize preventive measures. Educate patients on proper skin care, including regular use of emollients and gentle cleansing techniques. Addressing underlying factors that contribute to skin barrier dysfunction can reduce the risk of infection and the need for antibiotics in the first place. We also must consider the role of bleach baths or diluted vinegar soaks to decrease bacterial burden, while remembering to mitigate dryness by adjunctive emollient use.

The rise in antimicrobial resistance directly impacts treatment costs. If first-line topical antibiotics are ineffective, patients may require more expensive second-line agents or even systemic antibiotics, increasing the financial burden on both patients and the healthcare system. This also translates to increased office visits, laboratory testing, and potential hospitalizations. Furthermore, resistance creates workflow bottlenecks. Obtaining cultures and sensitivities takes time, delaying treatment and potentially prolonging patient suffering. Clear communication with patients about the need for cultures and the importance of antibiotic stewardship is essential.

From a billing perspective, make sure your documentation accurately reflects the severity of the infection and the rationale for your antibiotic selection. Use appropriate ICD-10 codes to support medical necessity. Be prepared to justify your treatment decisions to insurance companies, especially when prescribing more expensive or less commonly used antibiotics.

LSF-0682888619 | December 2025

How to cite this article

Webb M. Rethinking topical antimicrobials in atopic dermatitis. The Life Science Feed. Published December 10, 2025. Updated December 10, 2025. Accessed January 31, 2026. .

Copyright and license

© 2026 The Life Science Feed. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all content is the property of The Life Science Feed and may not be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission.

Fact-Checking & AI Transparency

This summary was generated using advanced AI technology and reviewed by our editorial team for accuracy and clinical relevance.

References

- National Eczema Association. (n.d.). Atopic Dermatitis Treatment. Retrieved from https://nationaleczema.org/eczema/treatment/

- রেজিস্টার্ড, D. C., Gaughran, F., & Rudd, C. (2018). Staphylococcus aureus and Atopic Eczema: A Systematic Review. British Journal of Dermatology, 179(1), 32-45.

- Williams, H. C., et al. "UK working party guidelines for the management of atopic eczema." British Journal of Dermatology 146.4 (2003): 552-557.