Rectoprostatic fistula after prostate cancer treatment is rare, consequential, and technically demanding. Prior pelvic radiation impairs vascularity and healing, raising the stakes for any attempt at definitive repair. In this context, the report of a robotic-assisted repair offers a pragmatic window into how teams sequence workup, decide on surgical access, and apply reconstructive principles to optimize success.

Beyond a technical tour, the narrative highlights the clinical reasoning clinicians can borrow: confirming anatomy, calibrating diversion and timing, excising devitalized tissue, and layering tension-free closures with a robust, well-vascularized interposition flap. These steps are not novel individually, but executed in concert via a robotic platform, they illustrate a path to functional recovery in an irradiated pelvis.

Robotic repair of post-brachytherapy rectoprostatic fistula: clinical reasoning and operative principles

Rectoprostatic fistula is an uncommon yet impactful complication in the prostate cancer care continuum. When it follows brachytherapy, the fistula increasingly reflects radiation-induced endarteritis, fibrosis, and impaired tissue healing. The clinical challenge is twofold: first, to map anatomy with precision and stabilize the patient; second, to execute a definitive repair in a hostile tissue bed where conventional rules of wound healing are strained. A robotic-assisted approach can help reconcile these demands, providing deep pelvic visualization and dexterity that favor meticulous debridement, multilayer closure, and safe interposition of vascularized tissue between the urinary and gastrointestinal tracts.

This case report foregrounds a pragmatic sequence: make the diagnosis confidently, define the tract and surrounding tissue quality, decide on diversion and timing, and plan a robotic repair that privileges vascularized coverage. While specifics vary by patient and fistula characteristics, the reasoning steps and operative priorities translate broadly to radiation-associated rectourethral or rectoprostatic fistulas.

Presentation and workup: stabilizing the patient and defining the problem

Patients with radiation-associated rectoprostatic fistula often declare themselves with a recognizable constellation of symptoms: pneumaturia, fecaluria, recurrent urinary tract infections, malodorous urine, tenesmus, or passage of urine per rectum. Pain may be perineal or pelvic and can be exacerbated by infection. In the setting of prior prostate radiation, even modest lower urinary tract symptoms deserve heightened suspicion when cross-tract contamination is present. Because radiation injury evolves over time, onset can be delayed, and symptoms may fluctuate with superimposed infections.

Initial priorities are sepsis control and source containment. Broad-spectrum antibiotics are reasonable when infection is suspected, with de-escalation guided by cultures. Early urinary drainage with a urethral catheter or suprapubic tube helps reduce pressure across the fistula. Fecal diversion is a key consideration: it lowers fecal load and contamination, potentially improving tissue conditions for later reconstruction. In irradiated tissue, diversion is commonly part of the strategy, whether performed up front or at the time of definitive repair, acknowledging that timing depends on clinical stability, nutritional status, and local inflammation.

Defining the fistula requires complementary diagnostics. Endoscopic assessment by cystoscopy clarifies urethral and bladder neck involvement and permits gentle evaluation of tissue quality, while flexible sigmoidoscopy or proctoscopy inspects the rectal side, identifies associated inflammation, and excludes proximal mucosal pathology. Contrast studies such as retrograde urethrography and voiding cystourethrography can outline the tract and demonstrate leakage patterns under physiologic conditions. Cross-sectional imaging, typically CT or MRI of the pelvis, maps the relationship between the rectum, prostate, and surrounding structures, detects abscess or sinus formation, and suggests the extent of radiation fibrosis. CT cystography can be particularly helpful when bladder involvement is suspected; MRI pelvis offers superior soft-tissue characterization to gauge fibrosis and the viability of planes for dissection.

Radiation pathobiology contextualizes these images. Endarteritis obliterans reduces perfusion, fibroblasts are less responsive, and collagen architecture becomes disordered. The combined effect is poor reserve for healing and a tendency toward breakdown at suture lines, especially if tension is present. Accordingly, preoperative optimization focuses on controlling infection, correcting anemia and malnutrition, and allowing inflammation to subside. Nutrition is not an afterthought; in prolonged or complicated courses, targeted nutritional support and stringent glycemic control can shift the odds toward durable closure.

Oncologic status matters. Persistent or recurrent disease can alter goals of care, dictate resection margins, or change the operative plan entirely. If cancer control is uncertain, a careful review of surveillance data and, if needed, targeted biopsy are justified before embarking on definitive fistula repair. The aim is a single, well-timed reconstructive effort rather than a series of salvage attempts in suboptimal conditions.

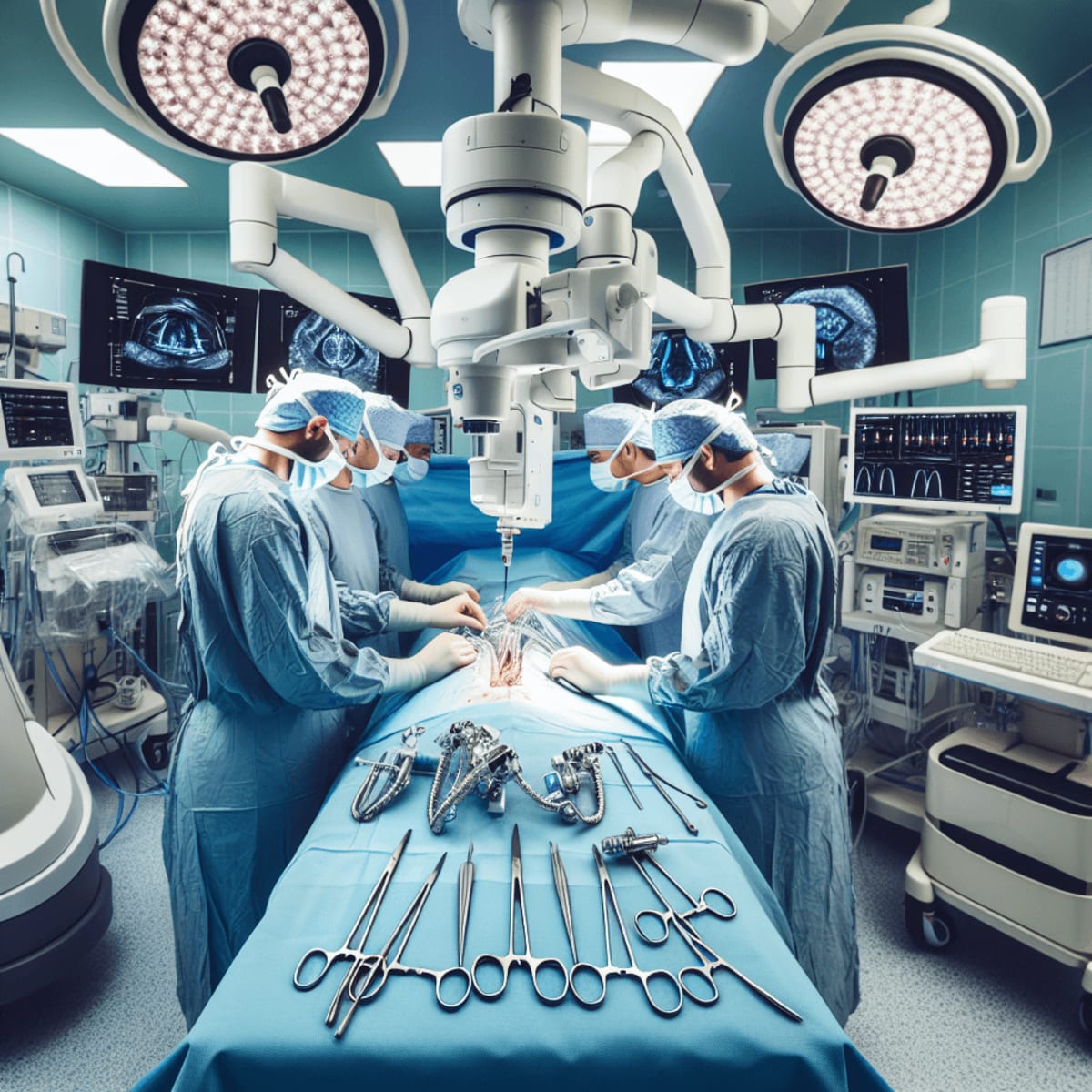

Operative strategy: why a robotic platform and how to execute

A robotic-assisted approach offers several advantages in the irradiated pelvis: magnified three-dimensional visualization of narrow planes; wristed instrumentation for precise suturing; and stable retraction that minimizes tissue trauma. For rectoprostatic fistulas, these features coalesce during key steps: careful posterior dissection between rectum and prostate, identification and debridement of the fistula tract, multilayer water-tight closures, and interposition of a vascularized flap to physically and biologically separate the repaired suture lines.

Positioning and access are tailored to teamwork between urology and colorectal surgery. The robotic cart positioning, port layout, and patient orientation are chosen to facilitate exposure of the deep pelvis and allow conversion to adjunct maneuvers without redocking. Adhesiolysis is performed with respect for irradiated tissue planes, recognizing that scar tethering may be dense and that bleeding, even if modest, is best avoided in a field where perfusion is already compromised. Intraoperative imaging adjuncts and dye tests can help confirm the tract, but their use is instance-specific and should be gentle to prevent exacerbating tissue injury.

Debridement targets only nonviable tissue while preserving as much healthy margin as possible on both rectal and urethral sides. The principle is to remove what cannot heal, not to pursue wide resection that would expand the defect. After debridement, attention turns to layered closure. On the rectal side, a two-layer closure is commonly favored where tissue allows: mucosal/submucosal approximation followed by a reinforcing seromuscular layer. On the urinary side, closure is usually performed in a meticulous, tension-free fashion with interrupted or barbed sutures as surgeon preference dictates, ensuring anatomic restoration of the prostatic urethra or bladder neck. Regardless of suture choice, the imperative is a water-tight seal confirmed intraoperatively by a low-pressure leak test.

Interposition is the cornerstone in radiated fields. A vascularized flap introduces perfused tissue to a biologically inhospitable zone, reduces the risk of suture line overlap, and fortifies the repair against recurrent breakdown. Options include a pedicled omental flap, a peritoneal flap, or, when perineal access is part of the plan, a gracilis muscle flap. Robotic mobilization of the omentum or peritoneum can be achieved through the same access, avoiding additional incisions. The chosen flap is oriented to cover the rectal repair and drape between rectum and urinary tract, with care to avoid twist or undue tension on the pedicle. Securing the flap with a few anchoring sutures helps maintain position and prevents migration.

Urinary drainage strategy is deliberate. A urethral catheter is typically left to stent the repair and maintain low-pressure drainage. In some scenarios, a suprapubic tube complements urethral drainage, offering redundancy and facilitating staged catheter management. Before concluding, the team reassesses hemostasis meticulously; in irradiated tissue, even minor bleeding can seed hematomas that threaten flap viability and healing.

Fecal diversion is often part of the management of radiation-associated fistulas. Whether diversion precedes the index repair or is performed concurrently is a function of sepsis control, tissue quality, and the anticipated complexity of reconstruction. Diversion reduces bacterial load and mechanical stress on the rectal closure, but it is not a substitute for sound debridement and flap coverage. If colorectal resection is indicated due to severe rectal injury or stricturing, a tailored segmental resection may be performed, though the default goal remains preservation and repair when feasible.

Robotic assistance does not obviate the need for surgical judgment; it augments it. Intraoperative decisions hinge on what the tissue will allow. If the rectal wall is fragile or the urinary tract cannot be closed without tension, the prudent move is to revise the plan: increase diversion, augment coverage, or stage the reconstruction. A successful outcome often reflects restraint as much as action.

Postoperative course, surveillance, and lessons learned

After reconstruction, management focuses on protecting the repair and validating healing before stepwise liberation from drains and diversion. Low-pressure urinary drainage is maintained for a defined period, with cystographic assessment prior to catheter removal to confirm no extravasation. Similarly, if fecal diversion is in place, timing of stoma reversal follows objective confirmation of rectal integrity, typically via flexible sigmoidoscopy, contrast enema, and clinical assessment. Premature reversal risks undoing the reconstructive gains, while excessive delay can impose unnecessary morbidity; balance is key.

Infection control remains a priority. Antibiotic courses are tailored to culture data and clinical trajectory, avoiding prolonged empiric therapy without indication. Pain control emphasizes multimodal strategies to reduce opioid exposure, support mobilization, and curtail ileus. Early ambulation, venous thromboembolism prophylaxis, and pulmonary hygiene mirror best practices in pelvic surgery. Nutrition continues to matter long after skin closure; protein-calorie repletion and micronutrients that support collagen synthesis can be the difference between a robust repair and a late breakdown.

Functional outcomes are individualized. Urinary continence may be preserved or may require rehabilitation depending on the preoperative baseline, extent of dissection, and urethral involvement. Erectile function, already vulnerable after radiation, can be further affected; counseling and targeted therapies should be part of the postoperative plan. Bowel function typically normalizes with time, though vigilance for strictures, urgency, or leakage after stoma reversal is warranted. The care team should set expectations early and review signs that merit re-evaluation, such as recurrent pneumaturia or UTIs, new perineal pain, or rectal bleeding.

Clinical follow-up pairs symptom review with selective imaging. A normal cystogram or MRI provides reassurance but is not a license to ignore subtle clinical cues. When doubt arises, low-threshold re-imaging is justified in a previously irradiated pelvis. Recurrent fistula is most often a function of residual tension, infection, or inadequate tissue interposition; recognizing these drivers guides any salvage strategy, which may range from re-diversion and reassessment to repeat repair with augmented coverage.

This robotic-assisted case underscores several durable lessons for teams managing radiation-associated rectoprostatic fistula:

- Patient selection and timing are strategic. Optimize infection control, nutrition, and inflammation before definitive repair.

- Anatomy drives the plan. Define the tract and tissue quality with complementary endoscopy and imaging.

- Debridement is selective. Remove nonviable tissue but avoid expanding the defect beyond what closure will tolerate.

- Closure must be water-tight and tension-free. Multilayer rectal closure and meticulous urinary repair are non-negotiable.

- Interposition is essential in irradiated fields. Choose a well-vascularized flap and secure it thoughtfully.

- Diversion supports healing but does not replace sound technique. Use it to reduce load across suture lines and to stage care when needed.

- Robotic assistance enhances precision. It does not replace surgical judgment about what the tissue will allow.

From a systems perspective, coordination between urology and colorectal teams is as important as any instrument. Shared preoperative conferences, intraoperative handoffs, and postoperative pathways reduce variability and align goals. When feasible, concentrating complex fistula repairs in centers with both robotic expertise and high-volume reconstructive experience likely improves consistency, particularly for radiation-associated pathology where contingency planning is routine.

Evidence for best practice in this space is built largely from case reports and small series. Within that mosaic, robotic-assisted approaches have shown promise in minimizing incisional morbidity, facilitating delicate pelvic suturing, and enabling intraabdominal flap harvest without additional open incisions. The present report adds another carefully documented experience, reinforcing the principle set that governs durable repair in hostile fields: stabilize, map, debride selectively, close meticulously, and interpose robustly. When those steps are observed and the timing is right, even a radiated pelvis can accept a repair that stands the test of time.

Ultimately, what matters most is not the platform but the plan. Robotic assistance is a capable means to an end: safe exposure, precise dissection, and reliable reconstruction in a compromised environment. As teams refine protocols around diversion timing, flap selection, and surveillance, the path from fistula diagnosis to durable closure continues to clarify. This report helps trace that path, not by claiming novelty, but by showing how established principles can be executed effectively with robotic tools in a challenging clinical scenario.

LSF-4387905225 | November 2025

How to cite this article

Sato B. Robotic repair of post-brachytherapy rectoprostatic fistula. The Life Science Feed. Published November 27, 2025. Updated November 27, 2025. Accessed January 31, 2026. .

Copyright and license

© 2026 The Life Science Feed. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all content is the property of The Life Science Feed and may not be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission.

Fact-Checking & AI Transparency

This summary was generated using advanced AI technology and reviewed by our editorial team for accuracy and clinical relevance.

References

- Robotic-assisted surgical management of a post-brachytherapy rectoprostatic fistula: a case report. PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/41214600/.