Acute coronary syndromes are managed with rapid reperfusion and aggressive secondary prevention, yet post-infarct inflammation still shapes infarct size, myocardial salvage, and adverse remodeling. High-sensitivity CRP has long been a prognostic biomarker, but the question now is whether CRP itself is a modifiable driver of tissue injury in the hours after revascularization.

The CRP-STEMI randomized trial explores a mechanistically precise approach: extracorporeal removal of circulating CRP in the acute phase after primary PCI. Rather than broadly suppressing immune signaling, this method targets a single effector believed to amplify complement-mediated damage to jeopardized myocardium. The design and rationale illuminate a shift in interventional cardiology toward targeted inflammatory modulation, while leaving efficacy and safety to be established by outcomes.

From biomarker to target: selective CRP removal in STEMI

The idea that post-infarct inflammation is not merely epiphenomenal has gained traction across cardiology. In that context, moving from measuring CRP to actively lowering it is a notable pivot. The CRP-STEMI randomized trial operationalizes this concept by integrating selective CRP apheresis into the early care pathway after primary PCI for ST-elevation myocardial infarction. The biological wager is straightforward: if circulating CRP contributes causally to complement activation and cell clearance signals on injured but salvageable myocardium, then removing CRP quickly and selectively may reduce non-ischemic, immune-mediated tissue loss. This positions CRP not only as a risk stratifier but as a potential therapeutic target during a narrow, time-sensitive window.

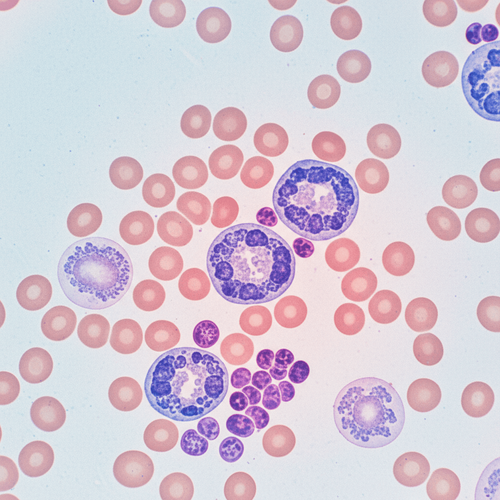

To understand what this approach intends to interrupt, it is essential to consider the dual roles CRP can play. As an acute-phase pentraxin, CRP rises in response to IL-6 and other cytokines and binds phosphocholine residues exposed by membrane disruption on necrotic and apoptotic cells. This binding can activate the classical complement cascade and opsonize cell debris, facilitating clearance. In sterile myocardial injury, however, these same processes may extend damage beyond the ischemic core. The trial, therefore, centers on the hypothesis that CRP is not solely a bystander signal of necrosis but a modifiable contributor to reperfusion-related extension of injury.

Time is central to the rationale. CRP typically begins to rise within hours of symptom onset and peaks around 24 to 48 hours. The early post-PCI period includes robust inflammatory signaling and microvascular dysfunction when salvageable myocardium remains at risk. If one could reduce circulating CRP concentration during this phase, the downstream interactions between CRP and complement components on exposed myocardial membranes might be attenuated. Selective apheresis, using an adsorptive column designed to bind CRP while sparing other plasma proteins, provides a means to test this hypothesis without suppressing broader immune pathways that are also necessary for host defense and healing.

In this paradigm, the intervention does not compete with reperfusion; it is designed to accompany it. The biological logic is complementary: recanalize epicardial flow and reduce thrombotic burden with PCI and antithrombotics, then temper a specific inflammatory effector that may exacerbate microvascular injury and infarct expansion. It is a different proposition from cytokine blockade or downstream inflammasome modulation. The aim is narrow: diminish the presence of CRP during a defined period to see whether measurable structural and clinical benefits follow.

Rationale and biological plausibility

At the heart of this strategy is the binding profile and effector functions of C-reactive protein. CRP recognizes phosphocholine on damaged cell membranes and complexes with C1q, initiating classical complement activation. This leads to C3 cleavage, opsonization, and, in some contexts, formation of the membrane attack complex. While such activity is adaptive in clearing microbial pathogens and necrotic debris, it may be maladaptive when it targets cardiomyocytes and extracellular matrix in peri-infarct zones that might otherwise stabilize.

Preclinical observations and clinical correlations converge on a few mechanistic points. First, CRP deposition has been found in infarcted myocardium alongside complement components, linking biomarker elevations with local effector activity. Second, higher CRP levels correlate with larger infarcts and worse left ventricular function across cohorts, even after adjusting for baseline risk. The association does not prove causation, but it anchors the notion that CRP is closely aligned with the processes that drive adverse outcomes. Third, the temporal relationship between the CRP peak and evolving myocardial injury suggests a plausible target window for intervention: not at the time of coronary occlusion, but during the inflammatory amplification phase following reperfusion.

Selective apheresis seeks to modify this biology by extracorporeal removal of CRP. Technically, the approach is akin to other adsorptive apheresis methods used in lipid disorders or toxin removal: whole blood or plasma is circulated through a column with ligand specificity for CRP, allowing substantial reduction in circulating levels during a treatment session. Because the column targets CRP, the method aspires to avoid the off-target immunosuppression associated with anti-cytokine therapies. The theoretical advantages include: preserving upstream host defense, minimizing drug-drug interactions with antiplatelets and anticoagulants, and enabling on-off control via session timing and duration.

The clinical relevance of this approach depends on several testable propositions. First, does selective removal of CRP in the acute phase reduce its myocardial deposition and complement activation locally? Second, does this translate into smaller infarct size on imaging, better left ventricular ejection fraction, or reduced microvascular obstruction? Third, can these structural benefits accumulate into fewer heart failure events, improved functional status, or reduced mortality at follow-up? Finally, is the procedure feasible in the real-time environment of primary PCI and early ICU care without delaying reperfusion or destabilizing patients?

Safety considerations are integral. Apheresis adds vascular access manipulation, extracorporeal circuit exposure, and potential hemodynamic shifts to an already complex post-PCI course. The trial framework accounts for feasibility and safety monitoring, including hemodynamics, bleeding, access-site complications, and potential interactions with antithrombotic therapy. Because CRP is a general marker of injury and infection, the balance between reducing harmful deposition in the heart and retaining adequate systemic host defense must be observed carefully, especially in patients with unrecognized infections or procedural complications.

It is also important to distinguish this strategy from chronic anti-inflammatory drug trials in atherosclerosis or post-MI care. Systemic agents that block IL-1beta signaling or modulate microtubule function reduce inflammatory tone over weeks to months and influence recurrent ischemic events. By contrast, selective CRP removal concentrates on the immediate pathobiology of the index infarct, aiming to limit acute myocardial injury rather than long-term plaque activity. These are complementary rather than competing biological targets, separated in time and mechanism.

Trial design and the questions it asks

Randomization and controlled exposure are crucial to separate signal from noise in the post-MI setting, where multiple contemporaneous therapies influence outcomes. The CRP-STEMI trial is described as a randomized evaluation of selective CRP apheresis added to standard-of-care management in ST-elevation myocardial infarction after timely reperfusion. This design directly tests whether a targeted, time-bound reduction in CRP can alter downstream measures that matter to patients and clinicians.

Endpoints in such a setting logically prioritize objective markers of myocardial injury and function. Imaging-based infarct size quantification, microvascular obstruction assessment, and left ventricular ejection fraction are natural candidates because they provide sensitive, mechanistically relevant readouts of tissue-level benefit or harm. Clinical events, including heart failure hospitalization and mortality, are essential but may require larger sample sizes or longer follow-up to detect differences, especially against the backdrop of modern PCI outcomes and secondary prevention.

Timing and logistics define the intervention. Because CRP begins to climb in the first several hours and may peak within 24 to 48 hours, the apheresis sessions must occur early and may need repetition to maintain reduced levels through the most vulnerable period. The protocol is designed to integrate sessions without delaying reperfusion, likely commencing after primary PCI and hemodynamic stabilization. These operational choices aim to test the biological hypothesis under conditions that reflect real-world catheterization laboratory workflows.

Patient selection is another key component. ST-elevation MI patients are heterogeneous: infarct territory, ischemic time, microvascular status, and comorbid conditions vary widely and influence both CRP kinetics and outcomes. The randomized design can accommodate this by stratifying or adjusting for key factors such as anterior versus non-anterior infarcts, symptom-to-balloon time, and baseline left ventricular function. Importantly, exclusion criteria customarily address hemodynamic instability that would render extracorporeal therapy unsafe, and conditions that confound inflammatory signals, such as active infection or systemic inflammatory disease, though the specifics are best interpreted from the protocol.

Analytical plans in these trials generally include intention-to-treat analyses to preserve the benefits of randomization and per-protocol sensitivity analyses to understand exposure-response relationships. Measuring achieved reduction in CRP during and after apheresis sessions, and relating those reductions to imaging or biomarker outcomes, can clarify whether a dose-response signal exists. Such correlations would help separate a true mechanistic effect from background variability in CRP kinetics after myocardial necrosis and reperfusion.

Feasibility metrics matter as much as efficacy in early investigations. These include success in initiating apheresis within target time windows, proportion of planned sessions completed, procedure duration, and the incidence of access-related or hemodynamic adverse events. If the approach is to have a future beyond controlled settings, it must prove compatible with the rapid, protocolized nature of primary PCI care pathways. The trial, by laying out its design and rationale, sets the stage for these critical operational questions to be answered alongside biological ones.

Finally, statistical power considerations shape what can be concluded. Imaging endpoints can improve power by reducing variance, but even then, trials must anticipate the background efficacy of contemporary reperfusion and adjunctive therapies. Neutral findings would need careful interpretation: was there insufficient CRP reduction, a missed therapeutic window, or a mismatch between CRP biology and clinically relevant injury pathways? Conversely, a positive signal on tissue-level endpoints would justify expanded testing toward hard clinical outcomes and perhaps tailored patient selection based on CRP kinetics or infarct features.

Implications for acute coronary care and future directions

The CRP-STEMI trial participates in a broader reframing of inflammation in ischemic heart disease. Over the last decade, evidence has shown that attenuating specific inflammatory pathways can reduce recurrent vascular events even when lipid levels and platelet activation are well controlled. In that landscape, selective CRP apheresis represents a different axis of intervention: a short-lived, device-based modulation of an effector molecule during the index event. If successful, it could join a small set of time-sensitive adjuncts layered onto reperfusion to limit infarct size and preserve function.

For clinicians, the practical implications would hinge on three questions. First, does the addition of CRP apheresis produce a measurable, reproducible reduction in infarct size or microvascular obstruction beyond what is achieved with rapid PCI and optimal antithrombotic therapy? Second, are the procedural demands compatible with the throughput and staffing realities of catheterization laboratories and coronary care units? Third, is the safety profile acceptable in patients who are already anticoagulated and exposed to vascular access risks?

Operationally, if efficacy is demonstrated, centers would need to map apheresis workflows to existing STEMI protocols. This might include a predefined trigger (e.g., confirmed STEMI after wire crossing and restoration of flow), a designated location (cath lab recovery area or ICU), and a team trained for rapid setup and monitoring. Device placement strategies would aim to minimize additional access sites or leverage existing venous access. Close coordination with anticoagulation regimens would be essential to limit bleeding, and standard post-PCI monitoring would be expanded to include extracorporeal circuit surveillance.

Patient selection could evolve as data emerge. If benefits concentrate in specific phenotypes (for example, larger anterior infarcts, high early CRP responders, or those with extensive microvascular obstruction), precision application might optimize the benefit-risk profile and resource use. Conversely, if effects are broadly consistent across patient subgroups, simpler criteria would facilitate dissemination. Either way, biomarkers and imaging could help identify those most likely to benefit within the narrow post-reperfusion window.

The health-system perspective must consider cost, capacity, and training. Apheresis requires specialized equipment and staff expertise that are not universal in all PCI centers. If the therapy demonstrates significant reductions in infarct size translating to fewer heart failure admissions and improved survival, the downstream savings and quality-of-life gains could offset upfront costs. Absent clear clinical benefits, however, the added complexity would be hard to justify. Early health economic modeling would be informed by trial data on procedure time, complication rates, and effect sizes on structural and clinical endpoints.

Mechanistically, the trial also informs the field even if results are neutral. A failure to observe benefit despite substantial CRP reduction would argue either that CRP is a surrogate rather than a driver of injury in the acute phase, or that other, earlier inflammatory triggers dominate the pathophysiology of reperfusion injury. Such a finding would redirect attention toward alternative targets, such as endothelial glycocalyx preservation, neutrophil extracellular trap modulation, or complement inhibition at different nodes. Conversely, a positive result would validate CRP as a causal effector in sterile cardiac injury and open avenues for device and pharmacologic strategies that modulate the CRP-complement axis.

It is also worth situating this work alongside chronic anti-inflammatory strategies in coronary disease. Trials of IL-1beta inhibition and low-dose colchicine have shown that modulating upstream inflammatory pathways reduces recurrent ischemic events. Selective CRP apheresis, if efficacious, would add a periprocedural, event-focused layer that targets tissue preservation after the index occlusion is treated. The two approaches could be complementary: one preserves myocardium acutely; the other reduces future plaque-mediated events. Whether there is synergy or redundancy would depend on careful sequencing, patient selection, and safety monitoring.

From a translational outlook, the key unknowns are dose, timing, and duration. How low must CRP fall, and for how long, to meaningfully affect cardiac structure and function? Are one or two early sessions sufficient, or is sustained reduction through the peak window necessary? Can pragmatic criteria guide when to start and when to stop based on serial CRP measurements, hemodynamic status, and imaging? The current trial can illuminate these parameters by reporting achieved reductions, exposure-time profiles, and their correlation with mechanistic endpoints.

Finally, equipoise should remain firm until outcomes are known. Biological plausibility supports testing CRP removal, but it does not guarantee clinical benefit. The trial design described provides the structure to answer whether the promise translates into improved myocardial salvage and patient outcomes. For the field, the value lies not only in whether the intervention works but also in what the results reveal about the role of CRP in human myocardial injury. Either way, the work advances the conversation about targeted inflammatory modulation in acute coronary care.

LSF-7456556133 | November 2025

How to cite this article

MacReady R. C-reactive protein apheresis in stemi: targeting inflammation. The Life Science Feed. Published November 29, 2025. Updated November 29, 2025. Accessed January 31, 2026. .

Copyright and license

© 2026 The Life Science Feed. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all content is the property of The Life Science Feed and may not be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission.

Fact-Checking & AI Transparency

This summary was generated using advanced AI technology and reviewed by our editorial team for accuracy and clinical relevance.

References

- Schneeweis C, Rauch G, Kemmler J, et al. Selective C-reactive protein apheresis in ST-elevation myocardial infarction: Design and rationale of the randomized CRP-STEMI trial. Clin Res Cardiol. 2024. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40738310/

- Ridker PM, Everett BM, Thuren T, et al. Antiinflammatory therapy with canakinumab for atherosclerotic disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(12):1119-1131. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1707914

- Tardif J-C, Kouz S, Waters DD, et al. Efficacy and safety of low-dose colchicine after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(26):2497-2505. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1912388

- Nidorf SM, Fiolet ATL, Mosterd A, et al. Colchicine in patients with chronic coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(19):1838-1847. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2021372

- Pepys MB, Hirschfield GM. C-reactive protein: a critical update. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(12):1805-1812. doi:10.1172/JCI18921