Upper and lower airway diseases frequently cluster, yet the extent to which they share a genetic and immunologic scaffold has been debated. By assembling robust evidence across nasal polyposis and asthma, new work delineates convergent loci and tissue enrichments that organize common mechanisms rather than isolated phenotypes.

The implications run beyond nomenclature. A coherent genetic architecture points to specific cells and pathways in the airway mucosa, refining our understanding of type 2 inflammation, barrier dysfunction, and leukocyte trafficking. This creates space for endotype-informed diagnosis, rational target selection, and the design of trials that better match interventions to biology. For clinicians and researchers, it offers a roadmap to connect genotype to tissue programs and, ultimately, to patient outcomes.

Shared genetic loci and tissue pathways across the airway continuum

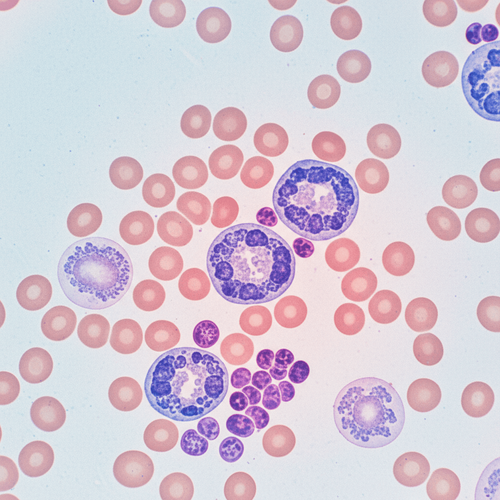

Asthma and chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) have long been linked by clinical comorbidity and biomarker overlap, but the extent of shared genetic determinants has been less clear. New aggregated evidence identifying 131 genetic loci converging on immunologic pathways and airway-relevant tissues reframes both conditions as points along a single biological continuum. Rather than treating upper and lower airway disease as separate entities, these findings align them under common mucosal programs that govern barrier integrity, epithelial alarm responses, and eosinophil-dominant inflammation.

At the heart of this synthesis is large-scale human genetics, including genome-wide association studies and downstream functional enrichment analyses. When multiple loci implicate the same cell types and pathways, the signal becomes more than the sum of individual variants: it becomes a map of disease-relevant tissue circuits. In asthma and CRSwNP, that map points strongly toward epithelial-immune crosstalk, type 2 cytokine cascades, and the chemotactic axes that organize tissue eosinophilia.

These convergent signals have practical consequences. They strengthen the case for endotype-driven classification, encourage cross-disease biomarker strategies, and provide a rational scaffold for prioritizing targets that operate upstream in the airway mucosa. The emphasis on tissue context also matters: when gene regulation is cell-type specific, the relevant interventions are those that meaningfully influence programs within those cells.

Convergent loci and the immunologic architecture

The most consequential aspect of identifying 131 loci is not the number itself but the pattern of biological convergence. Signals cluster in pathways consistent with an airway mucosal response: epithelial alarmins that initiate immune activation; cytokine axes that drive type 2 polarization; and adhesion, chemokine, and lipid mediator systems that choreograph eosinophil recruitment and survival. These elements define a coherent immunologic architecture that can explain both upper and lower airway clinical features.

- Epithelial alarm and barrier programs: Airway epithelial cells act as sentinels, releasing alarmins such as TSLP and IL-33 in response to environmental triggers. Genetic enrichment around epithelial signaling regions supports the idea that upstream activation at the barrier surface is a shared initiator in asthma and CRSwNP.

- Type 2 polarization: The type 2 cytokine milieu (e.g., IL-4/IL-13 and IL-5) drives hallmark features including IgE class switching, mucus metaplasia, and tissue eosinophilia. Loci converging on these pathways reinforce the primacy of type 2 inflammation across both conditions.

- Eosinophil trafficking and persistence: Chemokines, eicosanoid signaling, and adhesion receptors direct eosinophils into airway tissue and sustain them once there. Genetic enrichment in these axes is consistent with the eosinophil-dominant pathology seen in both nasal polyposis and many asthma endotypes.

While these pathways are familiar, the genetics lends weight and granularity: it moves the conversation from association by phenotype to shared causal anchors. The implication is that therapies influencing upstream epithelial signaling or the central type 2 cascade should have trans-disease relevance. Conversely, when signals are cell-type specific, precision in choosing the right intervention becomes paramount.

One underappreciated dimension is the role of gene regulation. Many trait-associated variants reside in noncoding regions that control cell-type specific gene expression. If regulatory variants are active in nasal polyp epithelium and bronchial epithelium alike, it strengthens the case that interventions altering epithelial programs can modulate disease in both compartments. This mechanistic unity helps explain clinical observations: patients with CRSwNP often exhibit severe or exacerbation-prone asthma, and biologics targeting type 2 pathways frequently show benefits in both conditions.

Finally, convergence at the pathway level supports integrated biomarker strategies. Peripheral eosinophil counts, fractional exhaled nitric oxide, serum IgE, and local tissue signatures often move together in type 2 endotypes. Genetics that points to a shared upstream engine justifies using these markers to identify patients who may respond to therapies across both asthma and CRSwNP, rather than siloing biomarker interpretation by site of disease.

Tissue and cell-type signals: upper-lower airway continuum

Pathway convergence is necessary but not sufficient. The strongest translational leverage comes from tissue and cell-type enrichments. When genetic signals are overrepresented in specific cell types, they help pinpoint where in the airway ecosystem disease programs reside and where interventions are most likely to succeed.

- Airway epithelial compartments: Enrichment in epithelial regulatory regions highlights barrier integrity, ciliary function, and mucus dynamics as core elements. In CRSwNP, epithelium overlying polyp tissue frequently shows remodeling and goblet cell hyperplasia; in asthma, similar programs correlate with airflow variability and mucus plugging. The genetic imprint suggests a shared epithelial script across the airway.

- Innate lymphoid and T helper lineages: Signals implicating innate lymphoid cells and Th2 effectors align with early and sustained type 2 responses. These cells are primed to respond to epithelial alarmins and sustain eosinophilic inflammation in both nasal polyps and bronchial mucosa.

- Eosinophils and granulocyte networks: Genetic enrichment in eosinophil-related pathways underscores chemotaxis, survival, and effector functions. This complements the histopathology of nasal polyps and eosinophil-predominant asthma.

- Endothelial and stromal niches: Recruitment and retention of leukocytes require vascular and stromal participation. Enrichment in these compartments points to adhesion and transmigration programs that could be leveraged therapeutically to reduce tissue eosinophilia.

The result is a tissue-centric model in which epithelial alarm, type 2 polarization, and eosinophil biology operate in concert across upper and lower airway sites. This helps reconcile disparate clinical pictures: a patient with CRSwNP and adult-onset asthma is not presenting two unrelated diseases but expressions of a shared mucosal program shaped by genetics and environment.

It is also a reminder that tissue sampling matters. Nasal tissue, accessible via endoscopy, may provide a practical window into lower airway biology when genetic and regulatory maps affirm shared programs. Conversely, bronchial sampling can clarify systemic versus local drivers in patients with refractory nasal disease. Tissue-aware diagnostics reduce noise and sharpen therapeutic choices.

These insights should also influence how we think about comorbidities and disease trajectories. If epithelial and immune circuits are genetically primed toward type 2 dominance, environmental exposures such as allergens, pollutants, or viral infections may more readily tip the system into chronic inflammation in both nasal and bronchial tissues. Understanding the tissue context can guide prevention and early intervention strategies, especially in patients with recognizable risk constellations.

Clinical translation: endotypes, targets, and trial design

The path from genetic signal to clinical impact runs through endotypes and targeted therapies. Convergent loci and tissue enrichments in asthma and CRSwNP reinforce three connected translation themes: endotype-driven care, target prioritization, and smarter trials.

Endotype-driven care: Clinicians already use biomarkers to align patients with anti-type 2 biologics in asthma, and increasingly in CRSwNP. A genetics-informed framework supports standardizing this approach across the airway continuum. When genetic convergence indicates a shared epithelial and type 2 engine, the following practical steps follow:

- Unified biomarker triage: Use eosinophils, exhaled nitric oxide, and IgE coherently across asthma and CRSwNP evaluations, recognizing that elevations often reflect the same upstream biology. Tissue biopsy in CRSwNP can add local confirmation when needed.

- Phenotype plus tissue signal: Combine symptom profiles (e.g., persistent nasal obstruction, anosmia, adult-onset wheeze) with tissue-informed markers to categorize patients into type 2 high versus other endotypes.

- Cross-compartment response assessment: Measure outcomes in both nasal and bronchial domains when initiating targeted therapy; improvement in one often predicts benefit in the other when the underlying program is shared.

Target prioritization: When many loci point to epithelial alarm and type 2 cytokine pathways, upstream interventions are attractive. Agents modulating IL-4/IL-13 signaling, IL-5 pathways, or epithelial alarmins such as TSLP and IL-33 are natural candidates for cross-disease benefit. Genetic enrichment in eosinophil trafficking and survival pathways also supports approaches that reduce tissue eosinophilia by limiting recruitment or prolongation of survival in tissue niches.

Importantly, tissue-aware targeting does not imply a one-size-fits-all strategy. The same genetic architecture can produce variable phenotypes depending on environmental context and additional modifiers. This argues for flexible algorithms: begin with interventions that act on shared upstream programs in type 2 high endotypes, then iterate based on objective response across both nasal and bronchial outcomes.

Trial design and enrichment: Convergent tissue and pathway signals should influence how we design and interpret trials:

- Cross-disease enrollment: Include patients with asthma and comorbid CRSwNP when testing interventions that target shared epithelial or type 2 pathways. Measure co-primary or key secondary endpoints in both compartments.

- Biomarker enrichment: Enrich cohorts by objective markers of type 2 inflammation to raise the prior probability of observing treatment effects aligned with the genetic architecture.

- Tissue readouts: Incorporate nasal and bronchial epithelial transcriptomic or proteomic readouts, where feasible, to confirm on-target activity in the cell types implicated by genetic enrichments.

- Durability and exacerbations: Track exacerbation rates and time-to-relapse measures in both airway sites; reductions in eosinophilic activity at the tissue level should translate into clinically meaningful stability if the genetic map is guiding the right targets.

Equity and generalizability: Genetic architectures and their clinical expression can vary by ancestry and exposure history. Incorporating diverse populations into discovery and replication cohorts matters, as does validating biomarker thresholds across groups. From a translational perspective, it ensures that endotype-driven strategies do not overfit to a narrow subset of patients.

Safety and mechanistic coherence: Targeting upstream epithelial-immune crosstalk can have broad effects. Safety monitoring should be aligned with mechanism: interventions that modulate alarmin signaling may influence host defense; therapies that reduce eosinophils can modify tissue repair dynamics. Trials should predefine safety signals and mechanistic biomarkers that reflect the implicated pathways, not just symptomatic outcomes.

From discovery to clinic: a practical arc

- Identify the shared program: Use convergent genetic signals and tissue enrichments to assert a working model: epithelial alarm leads to type 2 polarization and eosinophilic infiltration across upper and lower airways.

- Match biomarkers to program: Deploy eosinophils, exhaled nitric oxide, and local tissue signatures to stratify endotypes consistently across asthma and CRSwNP.

- Select upstream targets: Prioritize interventions acting on epithelial alarmins or central type 2 cytokine pathways when biomarkers indicate a shared program.

- Measure across compartments: Evaluate objective improvement in both nasal and bronchial endpoints to confirm that the intervention addresses the shared biology.

- Iterate with tissue insight: If response is incomplete, consider adjuncts that affect trafficking, adhesion, or stromal niches based on the enriched pathways, and reassess tissue readouts where feasible.

For clinicians, the operational takeaway is straightforward: when asthma and CRSwNP co-occur with biomarkers of type 2 inflammation, it is reasonable to frame them as a unified airway endotype and select therapies with cross-compartment efficacy. For researchers, the task is to translate the 131 loci into mechanistically coherent interventions by confirming cell-type specific gene regulation, testing on-target modulation in tissue, and embedding these insights into trial design.

These directions will not capture every patient. Non-type 2 endotypes, mixed inflammatory patterns, and structural or infectious drivers require different approaches. Yet the value of the convergent genetic map is to clarify where shared mechanisms are most likely and to guide precision in those scenarios, rather than relying on broad phenotype labels alone.

Ultimately, organizing asthma and CRSwNP around shared genetic and tissue programs opens a pragmatic path toward endotype-driven care: use biomarkers that reflect the implicated pathways, choose targets that address the convergent nodes, and confirm benefit across the airway continuum. As more loci are functionally annotated and mapped to specific cell states, the precision of this approach should improve, sharpening our ability to predict who benefits, from which therapy, and in which tissue context.

Source: PubMed record.

LSF-8277827195 | November 2025

How to cite this article

MacReady R. Shared genetic loci link nasal polyposis and asthma pathways. The Life Science Feed. Published November 27, 2025. Updated November 27, 2025. Accessed January 31, 2026. .

Copyright and license

© 2026 The Life Science Feed. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all content is the property of The Life Science Feed and may not be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission.

Fact-Checking & AI Transparency

This summary was generated using advanced AI technology and reviewed by our editorial team for accuracy and clinical relevance.

References

- 131 genetic loci highlight immunological pathways and tissues in nasal polyposis and asthma. PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/41213931/.