The dogma in critical care for years has been "early and aggressive" enteral nutrition (EN) in septic shock. Get those calories in, support the gut barrier, prevent bacterial translocation - that's what we were taught. But a growing body of evidence is starting to question this one-size-fits-all approach. Maybe, just maybe, the gut itself has something to say about when it's ready to receive nutrients.

A recent paper adds fuel to the fire, suggesting that delaying EN in select patients with septic shock might actually be beneficial. This isn't just about feeding tubes; it's about a fundamental shift in how we approach critical illness: moving away from rigid protocols and towards a more individualized, physiology-driven model. Are we finally listening to the patient, rather than the guidelines?

Clinical Key Takeaways

lightbulb

- The PivotEarly, aggressive enteral nutrition in septic shock, a long-held tenet, might not be universally beneficial; individualized assessment of gut function is crucial.

- The DataStudies suggest that delaying EN in specific septic shock patients may be associated with reduced mortality compared to immediate initiation.

- The ActionClinicians should assess individual patient physiology (e.g., bowel sounds, abdominal distension, vasopressor requirements) before initiating EN in septic shock, rather than adhering to a fixed timeframe.

Guideline Contradictions

Current guidelines, such as those from the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM), generally recommend initiating enteral nutrition within 24-48 hours of admission to the ICU for patients with septic shock. This push is rooted in the belief that early feeding supports gut integrity and reduces the risk of complications like bacterial translocation. However, these recommendations are largely based on studies with heterogeneous patient populations and varying degrees of illness severity. The emerging evidence suggests that a blanket approach may be doing more harm than good in certain subgroups. This directly challenges the 'one size fits all' approach that has been the bedrock of critical care feeding protocols for decades. The question now becomes: can we identify the patients who will truly benefit from early EN, and those who need a more cautious, individualized approach?

The Gut Microbiome Connection

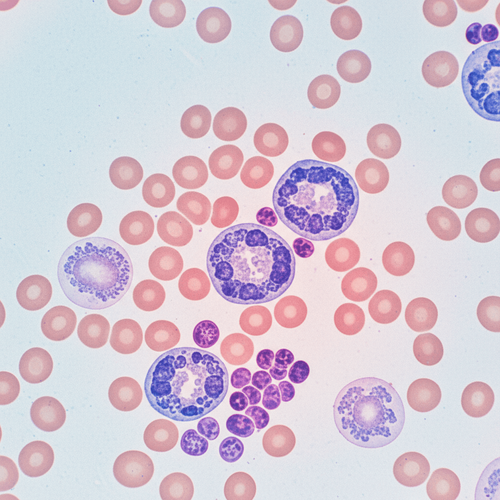

Why might delaying enteral nutrition be beneficial in some patients? The answer likely lies in the complex interplay between the gut microbiome, intestinal permeability, and systemic inflammation. In septic shock, the gut often becomes ischemic and dysfunctional, leading to impaired motility and increased permeability. Pumping nutrients into a compromised gut could exacerbate inflammation and promote bacterial translocation, potentially worsening outcomes. Consider the patient who is profoundly hypotensive and requiring high doses of vasopressors. Their gut is likely poorly perfused. Feeding them at this stage might be akin to pouring gasoline on a fire. Instead, a period of gut rest, allowing for improved perfusion and recovery of intestinal function, might be a more rational strategy. Further research is needed to identify biomarkers that can accurately predict which patients will benefit from delayed EN. Serial lactate levels, stool studies, or even advanced imaging techniques could hold promise.

Study Limitations

Before we throw out the existing guidelines, it's crucial to acknowledge the limitations of the available evidence. Many of the studies suggesting a benefit from delayed enteral nutrition are retrospective, observational studies. This means they are prone to confounding and selection bias. It's possible that the patients who received delayed EN were simply sicker to begin with, and that the observed association with improved outcomes is not causal. Furthermore, the definition of "delayed" EN varies across studies, making it difficult to draw definitive conclusions. And, let's be honest, who is funding these studies? Are there biases at play that we're not seeing? A large, prospective, randomized controlled trial is needed to definitively answer the question of optimal EN timing in septic shock. But until that data is available, clinicians must rely on their clinical judgment and a thorough understanding of individual patient physiology.

Future Directions

The future of septic shock management is undoubtedly personalized. We're already seeing this trend in other areas, such as fluid resuscitation and vasopressor selection. The same principle applies to nutrition. Instead of blindly following protocols, we need to develop tools and strategies to assess individual gut function and tailor our feeding strategies accordingly. This might involve using biomarkers to identify patients at high risk of gut dysfunction, or employing advanced monitoring techniques to assess intestinal perfusion and motility. Ultimately, the goal is to "listen to the gut" and provide nutrition when it's ready to receive it. And maybe, just maybe, this approach will lead to improved outcomes for our sickest patients.

Delaying enteral nutrition, even if clinically beneficial, presents workflow challenges. It requires more frequent reassessment of patient's readiness for feeding, potentially increasing nursing workload. Moreover, if delayed EN necessitates prolonged parenteral nutrition (PN), this adds significant cost. PN is far more expensive than enteral feeds, and carries its own risks, including catheter-related bloodstream infections. Hospitals need to develop protocols for assessing gut function and documenting the rationale for delayed EN to justify the increased cost and resource utilization. There may also be pushback from dietitians and other healthcare professionals who are accustomed to the traditional "early and aggressive" approach. Education and clear communication are essential to ensure that all members of the team are on board with the new paradigm.

LSF-5278659108 | January 2026

How to cite this article

MacReady R. Is early enteral nutrition always best in septic shock?. The Life Science Feed. Published January 9, 2026. Updated January 9, 2026. Accessed January 31, 2026. .

Copyright and license

© 2026 The Life Science Feed. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all content is the property of The Life Science Feed and may not be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission.

Fact-Checking & AI Transparency

This summary was generated using advanced AI technology and reviewed by our editorial team for accuracy and clinical relevance.

References

- Singer, P., Blaser, A. R., Berger, M. M., Alhazzani, W., Calder, P. C., Casaer, M. P., ... & van Zanten, A. R. (2019). ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition in the intensive care unit. Clinical Nutrition, 38(1), 48-79.

- McClave, S. A., Taylor, B. E., Martindale, R. G., Warren, M. M., Johnson, D. R., Braunschweig, C., ... & American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. (2016). Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 40(2), 159-211.

- Rice, T. W., Mogan, S., Hays, M. A., Bernard, G. R., Jensen, G. L., Wheeler, A. P., & National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network. (2012). Randomized trial of initial trophic versus full-energy enteral nutrition in mechanically ventilated patients with acute respiratory failure. Critical Care Medicine, 40(5), 1437.