Hepatocellular adenomas (HCAs) in adolescents are rare, and their occurrence should prompt clinicians to consider underlying genetic predispositions. While most HCAs are linked to oral contraceptive use or anabolic steroid use, a subset arises from germline mutations predisposing to tumorigenesis. A recent case highlights the importance of considering Ataxia-Telangiectasia Mutated (ATM) mutations in young patients with HCAs, especially when coupled with specific somatic mutations.

This single case isn't enough to change guidelines, but serves as a critical reminder. ATM is a DNA repair gene; mutations in ATM increase cancer risk, and early diagnosis of such predispositions in young patients could drastically alter monitoring and therapeutic strategies.

Clinical Key Takeaways

lightbulb

- The PivotIn young patients with HCAs, particularly with no clear risk factors, consider underlying germline mutations like ATM. Don't default to lifestyle factors alone.

- The DataThis case showed that HCAs with ARID1A mutations may indicate an underlying DNA repair deficiency, specifically ATM germline mutation.

- The ActionIf a young patient presents with HCA, obtain a detailed family history and consider referral for genetic testing, especially if ARID1A mutations are present in the tumor.

Case Report

A recent publication details the case of an adolescent patient diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) arising from a hepatic adenoma. What makes this case notable is the identification of an ARID1A mutation within the tumor and the subsequent discovery of an ATM germline mutation in the patient. The patient had no typical risk factors for HCA, such as oral contraceptive or anabolic steroid use. This prompted further investigation, leading to the identification of the underlying genetic predisposition. This case underscores the necessity for clinicians to maintain a high index of suspicion for germline mutations in atypical presentations of liver tumors, particularly in younger patients. The presence of ARID1A mutations in the tumor may serve as a red flag, prompting further genetic evaluation.

Guideline Alignment

Current guidelines, such as those from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), primarily focus on surveillance and management of HCC in patients with cirrhosis or chronic hepatitis. While these guidelines address risk factors and surveillance strategies, they do not explicitly detail the approach to HCAs in adolescents or the role of germline genetic testing in such cases. This case highlights a gap in the existing guidelines. The AASLD guidelines recommend considering liver biopsy for atypical liver lesions, but do not provide specific guidance on when to pursue genetic testing. Given the potential implications for long-term management and family screening, incorporating recommendations for genetic evaluation in young HCA patients, particularly those with ARID1A mutations or lacking typical risk factors, would strengthen existing protocols. This contrasts slightly with EASL guidelines, which offer more detailed classifications of hepatic adenomas based on molecular markers, but still lack specific guidance on germline testing in adolescents with HCA.

Study Limitations

It's critical to acknowledge that this is a single case report, and generalizations from one observation are inherently limited. While the identification of the ATM germline mutation is significant, it does not establish a causal relationship between ATM mutations and HCA development in adolescents. Further research, including larger cohort studies and functional analyses, is needed to validate this association. Additionally, the study does not address the prevalence of ATM mutations in the broader population of adolescent HCA patients. Without such data, it's difficult to estimate the clinical utility of routine genetic testing in this population. Finally, the cost-effectiveness of widespread genetic screening for ATM and other DNA repair genes in young patients with HCAs remains unknown. Who is going to pay for this?

Clinical Implications

Identifying a germline ATM mutation has several implications. Firstly, it necessitates genetic counseling for the patient and their family members, as ATM mutations are associated with an increased risk of other cancers. Secondly, it may alter surveillance strategies, with consideration for more frequent imaging and screening for other malignancies. Thirdly, the presence of a DNA repair deficiency may influence treatment decisions should HCC develop. However, the limited data on the efficacy of specific therapies in ATM-mutated HCC necessitates a cautious approach. From a workflow perspective, this adds complexity to the diagnostic pathway. Hospitals need protocols for triaging young HCA patients for genetic evaluation and integrating these findings into multidisciplinary management plans. Insurers may initially resist covering the cost of genetic testing, especially in the absence of robust evidence. Clinicians will need to advocate for coverage based on the potential benefits for patient care and family screening.

From a financial toxicity perspective, the cost of genetic testing and subsequent surveillance can be substantial. It is important to discuss these costs with patients and families upfront and explore options for financial assistance. The psychological impact of identifying a germline mutation should not be underestimated. Patients may experience anxiety, fear, and uncertainty about their future cancer risk and the implications for their family members. Providing access to psychological support and counseling is essential.

LSF-2787683323 | December 2025

How to cite this article

O'Malley L. Atm germline mutations and liver adenomas in adolescents: a clinical reminder. The Life Science Feed. Published December 16, 2025. Updated December 16, 2025. Accessed January 31, 2026. .

Copyright and license

© 2026 The Life Science Feed. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all content is the property of The Life Science Feed and may not be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission.

Fact-Checking & AI Transparency

This summary was generated using advanced AI technology and reviewed by our editorial team for accuracy and clinical relevance.

References

- Balabaud, C., Bioulac-Sage, P., & Paradis, V. (2017). Benign liver tumors. In Hepatology: A Textbook of Liver Disease (pp. 1247-1273). Elsevier.

- Llovet, J. M., Kelley, R. K., Villanueva, A., Singal, A. G., Pikarsky, E., Roayaie, S., ... & Finn, R. S. (2021). Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 7(1), 6.

- Tanaka, Y., Nakatani, Y., Miyake, K., Shiode, Y., Eguchi, H., & Yamada, T. (2024). Hepatocellular carcinoma arising from adenoma with ARID1A mutation in an adolescent patient with ATM germline mutation. Journal of Pediatric Surgery Case Reports, 102, 101943.

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. (2016). EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of benign liver tumours. Journal of Hepatology, 64(2), 471-491.

Related Articles

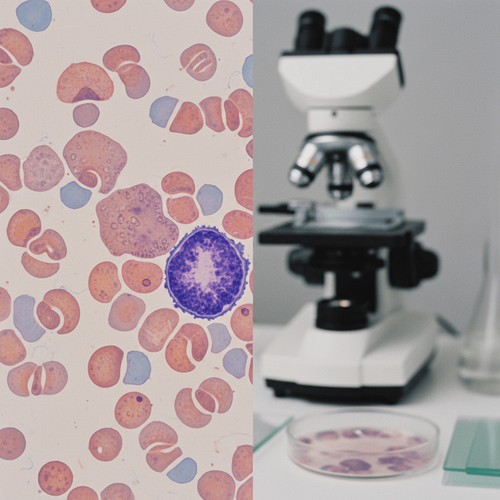

Navigating the Macrocytic Anemia Maze When You See Early Erythroblasts