Large-scale registries offer the promise of capturing rare disease epidemiology and treatment outcomes that randomized trials simply cannot. The European Society for Immunodeficiencies (ESID) registry, now spanning three decades and over 30,000 patients with inborn errors of immunity (IEI), represents a monumental effort. But are we drawing the right conclusions from this wealth of data?

A recent report summarizing key findings from the ESID registry deserves careful consideration. While the sheer volume of patient data is impressive, we must acknowledge the inherent limitations of registry-based research, particularly when applied to a moving target like IEI, where diagnostic criteria and treatment paradigms evolve rapidly. The devil, as always, is in the details - specifically, the biases.

Clinical Key Takeaways

lightbulb

- The PivotThis study underscores the phenotypic and genetic heterogeneity of IEI but does not fundamentally change diagnostic or treatment algorithms.

- The DataThe ESID registry reports on 30,628 patients over 30 years, but lacks granular data to perform meaningful subgroup analyses for specific IEI subtypes.

- The ActionClinicians should use registry data to inform, but not dictate, individual patient management decisions, prioritizing prospective clinical trials and mechanistic understanding.

Guideline Context

Current guidelines from the Clinical Immunology Society (CIS) and the European Society for Immunodeficiencies (ESID) emphasize early diagnosis and tailored management of IEI. These guidelines already acknowledge the vast heterogeneity within IEI and call for a personalized approach based on genetic diagnosis, immune phenotyping, and clinical presentation. Does this registry data change that? Not really. The sheer volume of data does not negate the need for careful clinical judgment. The ESID/CIS guidelines focus more on diagnostic approaches and algorithms and this paper does little to change that.

Cohort Evolution

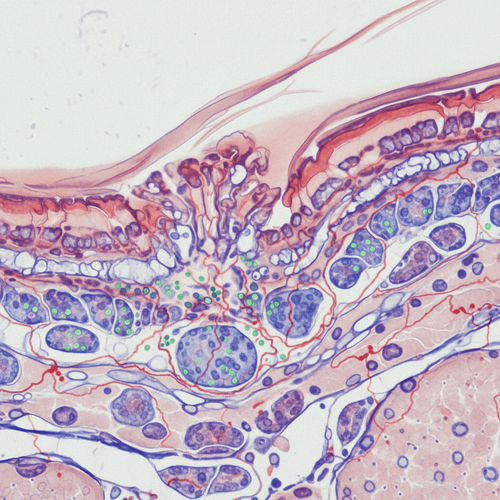

The ESID registry spans from 1994 to 2024, a period marked by significant advancements in diagnostic capabilities and treatment modalities. What constituted an "IEI" diagnosis in 1994 may be quite different from current criteria. For example, genetic testing has become far more accessible, leading to the identification of novel IEI subtypes previously categorized as idiopathic. Similarly, the introduction of biologic therapies and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) has dramatically altered the natural history of many IEIs. This temporal heterogeneity makes it challenging to draw meaningful conclusions about long-term outcomes across the entire cohort.

Geographic Generalizability

The ESID registry primarily captures data from European centers. While Europe represents a diverse population, the genetic architecture of IEI can vary significantly across different ethnicities and geographic regions. Extrapolating findings from a predominantly European cohort to other populations, such as those in Asia or Africa, requires caution. Access to specialized diagnostic and treatment centers also differs globally, potentially introducing selection bias. Do patients in lower-resource settings get the same level of diagnostic scrutiny and therefore are less likely to be captured in this registry? We simply don't know.

Limitations of Registry Data

Registries are inherently observational and prone to several biases. Selection bias is a major concern. Patients included in the ESID registry are likely those who have been diagnosed and referred to specialized centers, potentially excluding individuals with milder phenotypes or those who lack access to specialized care. Reporting bias is also a factor. Data entry relies on the accuracy and completeness of participating centers, which may vary over time and across institutions. Furthermore, registries often lack detailed information on confounding factors, such as socioeconomic status, environmental exposures, and comorbidities, which can influence outcomes.

Statistical Caveats

While the ESID registry boasts a large sample size, the statistical power to detect subtle differences within specific IEI subtypes may still be limited due to the rarity of individual conditions. Survival analyses are often employed to assess long-term outcomes, but these analyses can be influenced by censoring (patients lost to follow-up) and competing risks (death from other causes). The use of aggregate data can also mask important individual-level variations. A blanket "IEI" label hides a huge number of different genetic and phenotypic presentations.

The cost of diagnosing and managing IEI is substantial, involving specialized genetic testing, immunologic evaluations, and often chronic immunomodulatory or replacement therapies. Registry data may be used to justify resource allocation and reimbursement policies, but we need to be aware that incomplete or biased data could lead to misinformed decisions. Furthermore, the complexity of IEI diagnosis and management often requires a multidisciplinary team, including immunologists, geneticists, infectious disease specialists, and nurses. The ESID registry data does not account for these workflow considerations or the coordination challenges involved in providing comprehensive care.

LSF-1687589206 | December 2025

How to cite this article

Webb M. Registry data and inborn errors of immunity: use with caution. The Life Science Feed. Published December 27, 2025. Updated December 27, 2025. Accessed February 19, 2026. https://thelifesciencefeed.com/immunology/genetic-disorders/research/registry-data-and-inborn-errors-of-immunity-use-with-caution.

Copyright and license

© 2026 The Life Science Feed. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all content is the property of The Life Science Feed and may not be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission.

Fact-Checking & AI Transparency

This content was produced with the assistance of AI technology and has been rigorously reviewed and verified by our human editorial team to ensure accuracy and clinical relevance.

References

- Picard, C., et al. "2017 Inborn Errors of Immunity Classification, update by the International Union of Immunological Societies Expert Committee." Journal of Clinical Immunology 38.1 (2018): 96-128.

- Seidel, M. G., et al. "European Society for Immunodeficiencies (ESID) Registry Working Definitions for Clinical Diagnosis of Primary Immunodeficiencies: An Update 2022." Frontiers in Immunology 13 (2022): 857384.

- Tangye, S. G., et al. "Human Inborn Errors of Immunity: 2019 Update on Phenotypes and Genetic Mechanisms." Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 143.6 (2019): 1782-1793.

- Davies, J., et al. "Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for primary immunodeficiency diseases: European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation and Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases Working Party survey 2003-2017." Bone Marrow Transplantation 55.2 (2020): 308-318.

Related Articles

Cultural Nuances in Depression Diagnosis for Chronic Care Patients

The Natural History of Non-SCID T-Cell Lymphopenia: An Open Question