The quest to swiftly and accurately diagnose rare primary immune dysregulation (PID) disorders is perpetually hampered by their phenotypic heterogeneity. A new study attempts to address this via a machine learning model trained on IDDA2.1 phenotype profiles. The premise is sound: can an algorithm sift through complex clinical data to pinpoint these elusive diagnoses earlier?

While the initial results are encouraging, a critical appraisal is warranted. How robust is this model, really? Before we even consider integrating this into clinical practice, we must address concerns surrounding validation, potential biases, and generalizability. The devil, as always, is in the details.

Clinical Key Takeaways

lightbulb

- The PivotMachine learning models can potentially refine PID diagnosis, offering a faster route than traditional methods, but are not yet ready for prime time.

- The DataThe model achieved a promising accuracy in its training dataset, but external validation is needed to confirm its performance across diverse patient populations.

- The ActionClinicians should view these models as research tools, not replacements for expert immunological assessment, until more rigorous validation is completed.

Background and Rationale

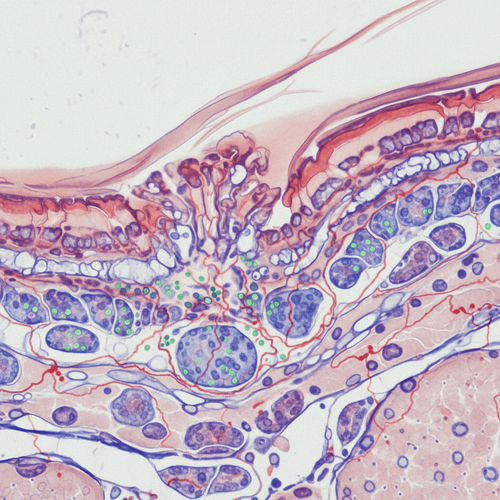

Primary immune dysregulation disorders, a subset of immunodeficiency syndromes, present a formidable diagnostic challenge. Their varied clinical manifestations often mimic other conditions, leading to delays in appropriate intervention. This is where machine learning steps in, theoretically. The IDDA2.1 phenotype profiling system aims to standardize data collection, and this study explores whether a machine learning model can leverage this standardized data to improve diagnostic accuracy. This approach, while innovative, must be viewed with a healthy dose of skepticism until its real-world performance is rigorously demonstrated.

Methodology: A Black Box?

The study employs a machine learning model trained on a dataset of patients with confirmed PID diagnoses, characterized by their IDDA2.1 phenotype profiles. The model's architecture and training process are adequately described, but the emphasis on internal validation leaves me wanting more. How well does this model generalize to patient populations outside of the training dataset? This is a critical question, especially given the inherent biases that can creep into any machine learning algorithm. We need to understand the features the model is prioritizing. Is it genuinely identifying disease-specific patterns, or is it simply picking up on confounding variables?

Results: Promising, but Provisional

The model reportedly achieves a high degree of accuracy in classifying PID subtypes within the training dataset. However, accuracy alone is a misleading metric. We need to examine sensitivity and specificity. What proportion of true positives are correctly identified, and what proportion of healthy individuals are incorrectly flagged as having a PID? Furthermore, a critical assessment of the model's performance across different PID subtypes is essential. Does it perform equally well for all disorders, or are there certain subtypes where its accuracy falters? Without this granular level of analysis, we cannot confidently translate these findings into clinical practice.

Limitations: The Crucial Caveats

The study's biggest limitation is its reliance on a single-center dataset. PID prevalence varies geographically and ethnically. A model trained on one population may not perform well in another. External validation using datasets from multiple centers is paramount. Furthermore, the sample size, while not insignificant, is still relatively small given the heterogeneity of PID disorders. A larger, more diverse dataset would significantly enhance the model's robustness and generalizability. What about the impact of missing data? Were imputation methods used, and if so, how might these have influenced the results? This is not addressed. And finally, who funded this? A clear declaration of funding sources is essential to assess potential conflicts of interest.

While machine learning-assisted diagnosis of PID holds theoretical promise, its current state raises several practical concerns. The cost of implementing and maintaining such a system, including data collection, algorithm training, and ongoing monitoring, would be substantial. Furthermore, reimbursement codes for AI-driven diagnostic tools are still evolving, creating uncertainty about cost recovery. Workflow integration presents another hurdle. How would this model fit into existing clinical pathways, and would it create new bottlenecks or inefficiencies? Patients should be counseled that this is an experimental diagnostic aid, not a definitive test.

LSF-7179869656 | December 2025

How to cite this article

Webb M. Machine learning and primary immune dysregulation: validation concerns. The Life Science Feed. Published December 26, 2025. Updated December 26, 2025. Accessed February 19, 2026. https://thelifesciencefeed.com/immunology/immunodeficiency/research/machine-learning-and-primary-immune-dysregulation-validation-concerns.

Copyright and license

© 2026 The Life Science Feed. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all content is the property of The Life Science Feed and may not be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission.

Fact-Checking & AI Transparency

This content was produced with the assistance of AI technology and has been rigorously reviewed and verified by our human editorial team to ensure accuracy and clinical relevance.

References

- Tang, Y., et al. (2023). Machine learning-assisted diagnosis classification of primary immune dysregulation using IDDA2.1 phenotype profiling. *Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology*, *152*(3), 678-687.

- Seidel, M. G., et al. (2020). European Society for Immunodeficiencies (ESID) Registry Working Definitions for Clinical Diagnosis of Primary Immunodeficiencies: Update 2020. *Frontiers in Immunology*, *11*, 586172.

- Picard, C., et al. (2018). International Union of Immunological Societies: 2017 Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases Committee Report. *Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology*, *141*(1), 6-19.

Related Articles

Cultural Nuances in Depression Diagnosis for Chronic Care Patients

The Natural History of Non-SCID T-Cell Lymphopenia: An Open Question